Construction Diary: Building a Forest Haven With Olson Kundig Architects (Part Two)

Editor's note: In 2011, Lou Maxon chronicled the process of building the Maxon House, featured in the September/October 2018 issue of Dwell. We're republishing the story of the decade-plus journey along with a video celebrating the stunning result.

Click here to read Part One of the series.

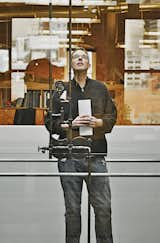

6. Visiting the Offices of Olson Kundig

Sixth floor. Ding. The doors slide open. Here I go.

I waited patiently in the lobby after being greeted by the receptionist. It was raining outside. The clouds were dark. It was your prototypical Seattle afternoon.

Located in the historic Washington Shoe Building in the Pioneer Square Historic District, the office design limits its impact on the preexisting space. The open plan layout is pulled away from the perimeter walls to limit contact with the existing historic structure and to take advantage of better natural daylight, circulation paths through the office, and to avoid the favoritism associated with the "corner office." Sustainable ideas were explored through the natural ventilation strategy (skylight and open stair for a chimney effect), not painting the warehouse walls or even the old windows (left "as is"), using masonite for floors and walls (a highly recycled content material left unpainted), and unpainted steel.

Tom walked over and introduced himself, and we soon settled into one of the conference rooms. An oversized pivot wall/door gently slid closed behind us, and we started chatting. There seemed to be instant chemistry picking up from where we’d left off on the phone. Tom would listen intently, then burst into ideas about the house. He shared stories and inspirations from other projects and experiences, connecting them to the opportunities he saw in our future dwelling. He was as kinetic as the architectural engineered gizmos he was known for.

We talked a bit about the scope of our project, and the "program" for the house. I wanted a main residence for a family of five, some sort of garage or area for cars and storage, and a studio or office space to work in, separate from the main residence.

I left the sixth floor that day with a heightened sense of euphoria and inspiration, my nervousness gone. Tom and I were on the same page. I had the sense this was going to be a wonderful journey.

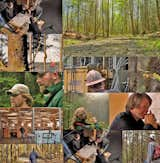

7. First Site Visit With Tom Kundig

It was a clear, sunny, spring Saturday in Carnation, the town 30 miles east of Seattle, where we’d purchased 21 acres. The site was in dismal condition and would require tremendous healing to truly realize its potential. It became evident that the lack of overhead light, the arching ceiling of diverse tree species blocking out the blue sky, and the dense forest all needed attention.

This was about seeing the forest through the trees. As we reached the vertical silver of the site’s sole view, we recalled visits from other architects: they all stood in this exact place pondering the same questions about where the house would go. This is where the experience differed with Olson Kundig. Tom kept walking. In fact, he turned the corner and walked right up to the edge of the slope, where the property dipped nearly 500 feet. He looked out on the potential view and spoke of how our house would embody the principles of prospect and refuge. One side (prospect) would open to the emerging view of endless farmland, winding rivers, the Olympic Mountain Range, and rich valley below—while the other (refuge) backs onto the dense forest.

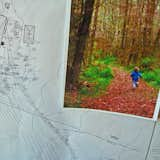

During the initial site visit, Olson Kundig Architects snapped some photos of us on the site. Here, a shot of Henry running down the existing logging road. It was obvious to us as clients that the architects understood early on that this was a house for not just my wife and me, but the entire family. Both Tom Kundig and Edward LaLonde from Olson Kundig embraced the challenge and involved the kids when appropriate in the entire process.

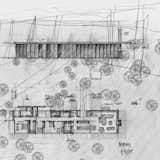

A rectangular volume, nearly 115 feet in length, was blocked out at that moment. We stood back and watched as Tom and our project architect Edward LaLonde mapped it out, weaving through the brush, tightrope-walking the slope edge, and starting to put the conceptual foundation together for our future home.

8. Developing the Maxon House Program

Before Olson Kundig Architects could get started on the design, we had to do some homework of our own. The first step was for my wife and I to measure out the spaces in our existing house and then come up with a wish list, or "program," for our future home. We needed to determine which spaces we wanted and what we could do without moving forward.

This effort was made easier by the fact that our house had sold, and the rooms were pretty much cleaned out and boxed up in preparation for our move to our rental house. It was clear after adding up the square footage in our existing space and then penciling out the wish list for the new house that we didn’t need substantially more space, just better designed space. One critical aspect of the program process was to remember that the program had to work not only for the day we moved in, but also be flexible enough to accommodate our family for the long-term.

When we started the search for an architect, we began keeping notebooks of tearsheets of different architects' work. Now that we had hired Olson Kundig Architects, we focused future notebooks on Kundig’s work, making notations on particular details and features we thought would be a good fit for our home.

9. Going Through County Reviews

We knew early on that the design was aggressive—the living and kitchen spaces floated above the sloping hill. In order to support the design, we’d need the blessing of the county—and the county, in turn, needed the blessing of approved geotechnical consultants.

We didn’t have the financial resources to do everything at once, so we often had to put the brakes on one element of the project in order to be able to afford the extra fees for an outside consultant. This ultimately ended up delaying the project.

We called in the services of Associated Earth Sciences, a multidisciplinary geotechnical engineering, hydrogeological, and environmental consulting firm. The objective was to determine the stability of the slope; that is, could it support the structure we were proposing? They drilled down for samples to analyze.

It feels a little like waiting to get a critical test result back from your doctor—pretty nerve-wracking. Ultimately, the geotechnical review came back in support of the design, with minor conditions regarding setback and buffers. The permit for critical areas was approved, and was valid for five years from the date that it was stamped. We had until Spring 2013 to start building.

10. Unveiling the Initial Design

Spring 2009 brought the next major evolution in the design of our home. We were presented with a set of schematic plans that reflected all the tweaks and evolutions in the design. We had settled on a big-picture vision of the house. All together, we got a four-bedroom, two and a half-bath home with a guest room, utility room, kitchen, living room, and library space. We didn’t want bonus rooms or unnecessary spaces that would add square footage without adding function.

Our final development area is around three to five acres of the entire 21 acre site. We have 16 acres of managed forest, which we are responsible for and cannot develop. Once you start adding all the elements of the site requirements such as the septic system, well, buffers, and setbacks for critical areas, things actually end up getting pretty tight. Fitting everything in is like a game of very intense Tetris. And there is a lot of pressure to get it right the first time.

11. Lessons Learned

One of the most direct questions we get from almost everybody is, "When do you break ground?" For someone not familiar to the process, it's a logical question. Why does it take so damn long to make this all happen? Here are a few things that any potential property owner or home builder may encounter along the way—along with some tips to keep you sane on your own personal home design journey.

Finances

First off, we had a house to sell before we could really throw money into new construction. This was Spring 2008, and luckily we were able to sell before the housing market took a steep dive. Beyond the proceeds from the sale, we'd have to set aside money for initial site reviews, a feasibility study, a deposit for the architect and contractors. We spent more over the years on geotechnical engineering, county permit fees, well drilling and installation, septic design and installation, and all the thinning and clearing work.

We didn't have the resources to write one big check, so having to spread out our cash outlay required adjusting our timetable and aligning our budget with critical milestones in the project. Sure, we could've gotten the project done quicker, but it wasn't an option financially.The key lesson for us was that we had to find partners that understood our position and were willing to work with us to make it happen.

Site and County (Permit) Issues

When we acquired the site, the only critical area identified was the steep slope—meaning that we had to have setbacks and buffers delineated on our site plan and approved by the county. We also had a forest management plan in place, so there were restrictions on developing a designated area of our property (which affected future issues, such as where to site the well and septic).

Getting permits to thin or cut took time—and then it took time to get contractors on site, and then get their work approved. This pushed out every other date on the timeline. At other times, weather set us back. Ultimately, though, we embraced the turtle pace and learned to really love and appreciate each line item.

Personnel Issues

People change jobs. We had multiple instances of getting to know our foresters, well drillers, civil engineers, and geotechs—only to see them leave their jobs (hopefully we didn't scare them from their respective career!). When someone finally gets to know you and the intricacies of your project, it takes time to hand off that work to someone new.For that reason, we've learned when engaging with consultants and the county that it's important to identify both your direct point of contact as well as the backup or supervisor to the contact.

12. The Big Reveal

Conceiving, planning, and ultimately building a project is an extremely risky venture. A good design and good planning gives you some insurance that when you ultimately walk into your house for the first time, it both meets your original desires as well as feels timeless for years to come.

Click here to see the completed Maxon House, and click here to read about the build from architect Tom Kundig's perspective.

Shop Tom Kundig Books

Published

Last Updated

Topics

Home ToursGet the Pro Newsletter

What’s new in the design world? Stay up to date with our essential dispatches for design professionals.