A Tiny Off-Grid Cabin in Remote Italy Is as Easy to Take Apart as It Was to Build

"Castagno," says architect Luca Scardulla emphatically, eyes shifting to teammate Federico Robbiano in search of the English translation. The two cofounders of Llabb Architettura, a firm based in Genoa, Italy, are describing the environment that surrounds a minimalist wooden structure they designed and built in nearby Tartago, Scardulla’s ancestral home.

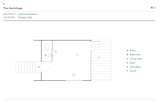

Situated in an old mountain village in Italy, the Hermitage is a 130-square-foot off-grid cabin made entirely of okoumé plywood. Llabb designed the retreat as a prototype that can easily be built in other remote locations. Here, it blends with fall colors as fog in the Trebbia Valley below rises. A corrugated metal sheet with two photovoltaic panels top the volume and power interior lights and electrical outlets.

The pair, both carpenters turned architects, mull over that word—castagno—then, in unison, call out "chestnut tree" and snap their fingers. An ancient chestnut forest shields views of the Trebbia Valley below Tartago, and cars that climb "curve after narrow curve" to get to the small town, which sits at the top of a mountain, Scardulla explains. "It’s really magical," Robbiano agrees, nodding.

Once you traverse roads bordered with mossy stone walls and towering trees, ascend the mountain, and meander through picturesque stone streets, the wooden retreat, called the Hermitage, reveals itself. It appears to hover in air, its sleek contemporary exterior a palate-cleansing surprise. The off-grid structure has razor-sharp lines and a contemplative air that recalls Japanese tea houses and Scandinavian cabins.

Built "in pursuit of flexibility," the 130-square-foot cabin, made entirely of okoumè marine plywood, is a prototype meant as an escape where guests can "easily concentrate on their thoughts and what they’re doing," Robbiano says. It can serve as a studio, a tea room, or simply a peaceful getaway—a place to recharge in nature.

The pair carefully placed the cabin to synch with the orientation of the village. Each of the ancient homes and buildings face the valley and take in expansive views, so their cabin does, too. To emphasize the cabin’s position, they used slats "that make it feel more horizontal," and keep it "floating toward the valley."

"It’s simple yet expressive," Scardulla says. "We don't like excess. We don’t like when you enter a space, and everything is immediately declared, and everything is clear. We like discovery and complexity. When you get here, and you get to the door, you have one perspective, and then you enter and get another, and so on."

Fully off grid and powered by rooftop solar panels, it treads lightly on the earth. "We haven't affected the land," says Scardulla. "There isn’t concrete. You can disassemble it, and the land becomes as it was before. For us, that was important; architecture is moving in that direction."

To build the cabin, Scardulla and Robbiano hosted an immersive workshop and retreat for Llabb’s six-member team to teach them about the building process. After four months of planning, they spent two weeks getting the materials to the tricky site and putting the pieces together. "Everybody did everything," Robbiano says.

"You can disassemble the cabin, and the land becomes as it was before. For us, that was important."

—Luca Scardulla, architect

Hosting a hands-on experience was important to Scardulla and Robbiano, because that’s how they got their start. The duo founded Llabb in 2013 as a carpenter’s workshop that made custom furniture before moving on to full-scale architectural projects. But their origins as self-taught craftsmen who began by building and designing bookshelves, tables, and chairs in their garage studio is reflected in the larger scale work they’re doing today.

Whether they’re building a bench or a home, the duo has pretty much always stuck with okoumé wood. "We used it a lot when we were carpenters—we are quite in love with it," says Scardulla. "It’s resistant to weather and easy to work with." When left untreated, the wood’s deep honey hue, a reddish color, becomes patinated with time. Since being built, the cabin has already taken on more of a gray color that matches the village’s old buildings.

To enter the cabin, guests first take two steps on heavy stones—the kind you might find at a Japanese tea house—before boarding a small bridge to the front door. Inside, the okoumé is sealed and used on every interior surface from ceiling to floor. "When you enter, the smell of the wood is strong." says Robbiano. "It’s like being in a sauna." Scardulla adds, "And the sound is deadened. It’s soft when you talk. The cabin is really its own experience."

Inside, an entry area "countertop" along the right wall acts as a seat, storage ledge, and workspace. It stretches the length of the cabin, directing a visitor’s eye to valley views. Stepping down into the main living area provides an even better view of the valley. An earthy green sofa provides day seating, and a foldout bed pulls down at night. The bathroom, tucked away near the front door, includes a compostable toilet, shower, sink, and hidden water tank.

"The space is small," says Scardulla. "The lines are few and are super clean. It’s really simple, yet when you enter and sit on the sofa, you can sense something special," Scardulla says. "There is something about the harmony of it all." Robbiano likes to use the space to work remotely, as it’s conducive to concentration. "There aren’t any distractions," he says. "You can always move your eyes from the computer to the window, then to the forest, which is relaxing. You think, ‘Okay, I am peaceful.’"

Today the firm rarely does its own joinery due to time constraints, instead relying on tradespeople to bring their custom designs to life. "We like to keep a tailor-made approach," says Scardulla. But with the Hermitage, he and Robbiano savored the opportunity to be hands on once again. And doing that with their team, they say, was the most rewarding part. "It wouldn’t have been the same had we been producing it for someone else; we would have focused more on the result," says Scardulla. "The result was satisfying, but the process is what sets this cabin apart."

Related Reading:

8 Scandinavian Cabins That Master the Art of Minimalism

30 Comforting Interiors That Have Us Pining for Plywood

Project Credits:

Architect of Record: Llabb Architettura / @llabb_architects

Published

Last Updated

Stay up to Date on the Latest in Tiny Homes

Discover small spaces filled with big ideas—from clever storage solutions to shape-shifting rooms.