Hollywood Craftsman Aerie

5 more photos

Credits

From Siddhartha Majumdar

As Russell Brown looked out onto the detached garage of his 1913 Los Angeles Craftsman home, he knew that the structure had seen better days. Seeing the potential in the extra square footage, which had become relegated to storage, Brown — a filmmaker who purchased the home in 2003 and lives with his boyfriend, Rory, and two pet cats — looked into the option of remodeling the original framework into an accessory dwelling unit (ADU).

Brown is no stranger to virtuosic architecture in its many forms. In 2019, he founded Friends of Residential Treasures: Los Angeles or FORT:LA, an award-winning nonprofit dedicated to telling Los Angeles' story through programming and self-guided tours that highlight historical residential architectural gems — some more well-known than others — from across the city's great expanse. So when it came to developing a vision for the remodel, he enlisted Anupama Mann from architecture studio Wyota Workshop to refurbish and expand the original structure using a methodology that both honors the home's original Craftsman construction and harmonizes with the natural elements of Brown's lush backyard.

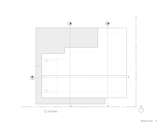

These natural elements were a key starting point for Mann. She observed the growth patterns of a towering Chinese Elm and a smaller yet established Japanese Maple, whose branches overhung one side of the original single-story garage. From here, the design began to take shape: working with the existing trees (and with restrictions from the Historic Preservation Overlay Zone (HPOZ) in which the Brown residence sits), Mann proposed a full remodel with a second story addition to the garage that would be indented, occupying half the width of the first floor's footprint.

Mann worked to maximize ceiling height in the ADU by insetting the second floor several feet into the ground floor, forming two volumes that join at a slight overlap. This element of the design becomes evident from the light-filled ground floor, where a distinctive ceiling clad with white oak and exposed steel structural beams reveals the second floor's footprint.

A contemporary reinterpretation of a spiral staircase creates egress between the two floors. Treads clad in white oak pinwheel around a central post made of pine in a unique enclosed rectilinear space that dictates the shape of each stair. Tall vertical windows offer views of the outdoors from different vantage points as one ascends or descends from one floor to the next.

The second floor's low pitched roof and overhanging eaves mirror the traditional craftsman shape of the original structure with a few decidedly modern updates. The same tonal dark gray-green color scheme is continuous throughout the structure's exterior, though Mann changed the scale of the vertical wood siding on the second floor to create a nuanced variation on the original design. "This subtle juxtaposition was a major goal for us," noted Mann. The second floor is also distinguished by a balcony with a steel guardrail that echoes the sidings's fluted design, as well as an exposed steel moment frame with vividly hued structural components that comprise modern, utilitarian accents.

The ADU makes tribute to Frank Lloyed Wright's ornamental window treatments with a trompe l'oeil picture window on the second floor. Inspired by a stay at Wright's 1958 Seth Peterson Cottage in Mirror Lake, Wisconsin, Brown entreated Mann to iterate on signature elements in the house to develop a custom design that uses rhombus-shaped panes to create the illusion of a bay window. The window offers an intimate encounter with the elm and maple trees outside, which filter dappled light throughout the space true to Mann and Brown's original vision. ”The palette of the garden was silvers and greens and the overall tone is meant to feel like an abandoned and overgrown garden on a remote and forgotten European island. The dwelling unit itself is supposed to feel like a treehouse," explains Brown. The lighthearted atmosphere of a treehouse comes to the fore for Mann, who reflects, "It has a playful element, a lack of reverence for the architecture. You can interact with it; you can reach up and touch things. It's a fun place to be."

A focal point of the design is the upstairs bathroom, which is made memorable with custom tilework by artist and architect Cha-Rie Tang, who creates ceramic tiles to order at her Pasadena studio. Muted rust, mustard and teal personify the design, which uses a multiplicity of differently sized squares and rectangles to frame a tactile rendering of a tree's creeping branches created in a nod to the building's surroundings and the 19th and 20th-century Arts and Crafts movement emphasis on designing with the natural world in mind. "You can argue that the larger principle under which any preservation lies is to work with and keep what you have," says Mann. "We expanded in our mind what falls under that concept as not just the built structure, but the landscape — the tree."