Important Resources on Redlining’s Role in Cementing the American Wealth Gap

Homeownership was the central pillar of the American dream in the 20th century, contributing to retirement security and generational wealth. Beginning roughly in 1945, returning veterans taking advantage of the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944—better known as the G.I. Bill—spurred a postwar building boom of midcentury homes that were meant to be more accessible for an expanding middle class. These ladder rungs to financial stability, however, remained out of reach in Black neighborhoods as property values declined due to a discriminatory practice known as redlining.

This six-minute clip from the acclaimed 2003 documentary series Race—The Power of an Illusion is a quick introduction to the policy; below, we’ve rounded up other informative resources that track the lasting impact of redlining.

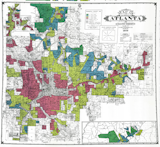

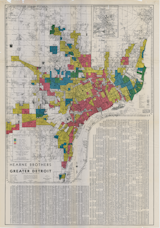

From 1935 until 1977, banks used "residential security" maps drawn by the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation to assess property values and guide their decisions on whether to lend money to clients for building, buying, and renovating homes. The maps graded neighborhoods from "Type A," marked in green, to "Type D," marked in red, and dictated where the government, bankers, and investors invested capital—and where they withdrew it. The biggest determining factor was the presence or absence of Black residents. For decades, low- and moderate-income and minority communities were intentionally cut off from lending and investment.

Originally created during the New Deal to rescue the collapsing housing market after the 1929 Wall Street crash, the maps offer a lesson in how government policy can have disastrously disparate impacts. In 1977 (almost a decade after Congress passed the Fair Housing Act in 1968, making housing discrimination illegal), the Community Reinvestment Act required banks to invest in communities in which they did business. The law was passed to combat the lasting effects of redlining. But the availability of loans and credit—and the exploitative terms of that credit, which led to the mortgaged-backed securities crisis of 2008—remains a huge obstacle in housing affordability to this day.

Drawing from research at the National Archives by teams of University of Richmond, Virginia Tech, and University of Maryland, Mapping Inequality is a searchable archive of redlining in cities across the U.S. Researchers obtained, digitized, transcribed, and geolocated data from historic maps, and the tool has nurtured ongoing scholarship at other universities and institutions. Its availability has led to significant local reforms of zoning laws—and bans on restrictive covenants upholding these racially discriminatory legacies.

For example, the University of Minnesota’s Mapping Prejudice project uses the data to indicate how demographic patterns set by redlining remain in place today, leading to disparities in employment, education, and health care. At the University of Washington, the Seattle Civil Rights & Labor History Project created Segregated Seattle, tracking the use of racial covenants on deeds. Language like "No person or persons of Asiatic, African or Negro blood, lineage, or extraction shall be permitted to occupy a portion of said property," for example, limited who could live in many Queen Annes.

The group Detroitography has images and analysis of the 1939 Detroit redlining map and other cartographic studies related to social justice issues. In Washington D.C., the Mapping Segregation project examines restrictive covenants and includes geolocated maps of FHA Insured Housing to trace redlining in the capital, as well as the crucial distribution of resources to schools.

The 2009 exhibit Red Lines Housing Crisis Learning Center at the Queens Museum by Damon Rich, partner at HECTOR and cofounder of Center for Urban Pedagogy, documented redlining on the New York City Panorama and screened The Road the Better Living, a 1959 film glorifying the benefits of homeownership for the emerging middle class and inadvertently revealing its discriminatory codes. Filmmaker and educator Walis Johnson’s The Red Line Archive used this history in a mobile public art project enacted along the boundaries of Brooklyn neighborhoods affected by gentrification and displacement.

Other studies have recently traced these legacies in Chicago—as analyzed by the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago—as well as in Boston, Los Angeles, and Philadelphia. Understanding of these facts underlies Ta-Nehisi Coates’s forceful 2014 Atlantic story, "The Case for Reparations," which argued that the dispossession of Black wealth was not just a historical legacy of slavery but part of an ongoing process that justifies reparations.

For longer reads, look to Richard Rothstein’s The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America, which unveils the systemic characteristics of redlining. Sam Stein’s Capital City: Gentrification and the Real Estate State looks at the legacy of redlining as it traces its way to the present day in New York, while Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor’s Race for Profit uncovers how exploitative real estate practices continued well after housing discrimination was banned. Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Between the World and Me deals with a variety of forms of institutional racism through the device of a letter to his son, and Sarah Bloom’s The Yellow House tells a personal story about her family home in New Orleans that was destroyed during Hurricane Katrina, inflected by narratives of ownership, dispossession, and place. Meanwhile, Moving Toward Integration: The Past and Future of Fair Housing by Richard Sander, Yana Kucheva, and Jonathan Zasloff offers a comprehensive chronology and analysis of American housing segregation—and efforts to address it over the past century and a half.

Start reading

Top image courtesy Mapping Inequality

This article was originally published on June 4, 2020. It was updated on February 7, 2025, to include current information.

Related Reading:

Published

Last Updated

Get the Dwell Newsletter

Be the first to see our latest home tours, design news, and more.